National Geographic: My Surreal Experience of Donald Trump's Election

Far away from America, future victims of the president's climate change policies watched his election on solar-powered TVs.

A kid naps in a “video store,” while news of Trump’s win comes in on the TV, courtesy of solar power. (Tim McDonnell)

This story first appeared on National Geographic Voices.

When Donald J. Trump was elected President of the United States, I was sitting in a tin-roofed, dirt-floored cafe on the shore of Lake Victoria, in a bustling Kenyan fishing village called Usenge, waiting for a ferry and watching the sun rise. It should have been a serene morning. It wasn’t.

I was trying to follow the election, but my phone’s battery was dying and I had terrible data reception. Occasionally a latent WhatsApp message would dribble in, or the New York Timeshomepage would refresh, but mostly I was in the dark. I was pacing the floor, swilling milky tea, jabbing at my phone, and muttering to myself like a lunatic. Whenever I heard the words “Trump” or “Clinton” on the Kiswahili-language radio, I would grab the nearest patron and beseech them to translate. They were hardly paying attention to the news; their conversations were about that day’s market prices for the anchovies and perch they were about to gather from the lake. I got mixed messages. Trump was up, then Clinton was up, something about Florida, about Michigan. None of it made any sense. But I could tell the news wasn’t good. Something had gone terribly wrong. Then my boat appeared, and I had to push off without knowing the conclusion.

The port village of Usenge, where I waited in vain for news about the US election. (Tim McDonnell)

There are plenty of reasons for plenty of people to fear what Trump’s presidency will entail. As the New Yorker’s David Remnick put it, “That the electorate has, in its plurality, decided to live in Trump’s world of vanity, hate, arrogance, untruth, and recklessness, his disdain for democratic norms, is a fact that will lead, inevitably, to all manner of national decline and suffering.” As a journalist, my focus is on climate change, so I am particularly sensitive to the “decline and suffering” that Trump will bring about in that arena. Trump is a climate change denier. He believesglobal warming to be a hoax “created by and for the Chinese to make U.S. manufacturing non-competitive”; he intends to withdraw the US from the global climate agreement reached in Paris in December; he is already staffing key environmental positions with climate change deniers and fossil fuel industry stooges; instead of limiting carbon dioxide emissions and speeding a transition to clean energy, he wants to bring back a renaissance of dirty, dangerous coal.

I found myself reciting this disturbing litany as I stepped into the ferry. It was a giant wooden canoe held low in the murky water with the weight of two dozen passengers, several pallets of flour, some burlap sacks of ice, a few woven baskets, a plastic table-and-chairs set, and some other odds and ends. We were destined for Mageta Island, an isolated fishing outpost on the lake near the Ugandan border. The fishers and traders on the boat with me were mostly Luo, the same tribe that produced Barack Obama’s forebears. A few of them were familiar with Hillary Clinton; most had never heard of Donald Trump (yes, such a place does still exist in the world). They just wanted to know when Obama could come “home” and be president of Kenya. It was a surreal setting in which to experience this shocking pivot in American history, especially because my companions were living on the front lines of an environmental phenomenon Trump pretends doesn’t exist. I was surrounded by the future victims of President Trump

The ferry to Mageta Island was filled with Luo people, the same tribe that produced President Barack Obama’s forebears. (Tim McDonnell)

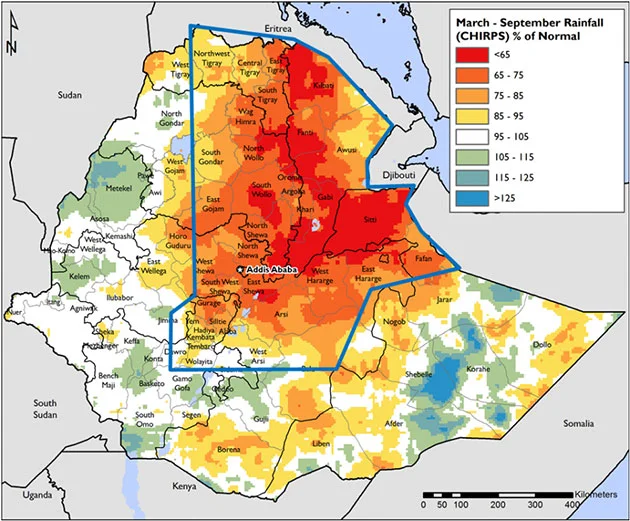

The fishery industry on Lake Victoria is already impacted by climate change. The lake, although Africa’s largest by area, is shallow, essentially a gigantic muddy puddle. During times that are hot and dry, the lake recedes, and fish seek cooler, deeper waters. Fishers catch less, so they earn less, so it becomes harder for them to feed their families and afford necessities like school fees and healthcare. Across East Africa, temperatures are rising (up nearly two degrees Fahrenheit since the 1960s on average), while seasonal rainfall becomes increasingly unpredictable and periods of drought become more common. As I am reporting this year through a Fulbright-National Geographic Storytelling fellowship, the impacts of these changes are widespread across African societies. In Kenya, one-fifth of the population, some 10 million people, are smallholder farmers and pastoralists who rely almost exclusively on rainfall to grow crops and support livestock for their subsistence and income. These people supply nearly 80 percent of the country’s agricultural output, which accounts for one-third of gross domestic product. When they suffer, all Kenyans suffer. Increasingly, their suffering can be traced to greenhouse gas emissions produced by the US, Europe, China, and other big polluters.

I had come to Mageta to report on a possible solution. A few years ago, a British start-up called SteamaCo installed a solar power micro-grid here, in the island’s main village. A few big solar panels sit atop a battery and and generator system, which connects via overhead cables to a selection of homes and businesses. Kenya’s main electric grid will never reach this place, and prior to the solar system the only source of power was diesel generators. These are dirty, loud, unreliable, and expensive, on the order of $5 per day to fuel and maintain. Power from the solar micro-grid is clean, reliable, and can be purchased for around $1.50 to $3 per day depending on usage

The solar system on Mageta Island was set up in 2009 by British start-up SteamaCo. (Tim McDonnell)

Solar systems like this can be an effective way to increase rural peoples’ access to energy, and allow for heavier uses than the small hand-held panels that people across East Africa commonly use to power cell phones and light bulbs. Several shops in Mageta had refrigerators, to chill food and sodas. There was a barbershop with electric razors, and computer kiosks where people can stay connected and even earn extra cash working for web-based services like Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. The main street now has security floodlights at night.

Rebecca Aluoch owned a shop selling cold drinks and blasting Ugandan pop hits from a boombox. The solar system is life-changing, she said.

“It facilitates sales,” she said. “I can work at night, anytime I want, and draw in customers with entertainment.

A barbershop and phone charging station, one of the several small businesses on Mageta Island that use power from the solar micro-grid. (Tim McDonnell)

In general, energy access allows people to diversify their incomes away from climate-sensitive industries like fishing. To be sure, millions of anchovies are still spread out in the sun to dry behind every house here, and the place smells a bit like the galley of a Blackbeard-era pirate ship. But now, a bad fishing season doesn’t necessarily mean an instant plunge into poverty. And while the emissions from the old diesel generators were negligible on a global scale, everyone prefers clean air to breathe in their own home. Mageta is an inspirational example of how measures to adapt to and mitigate climate change can come together to improve peoples’ quality of life and protect the environment.

Then I remembered Trump.

I wondered what he would make of this community. I expect he would see nothing of value here. A post-election nosedive in solar industry stock prices is enough to tell you what he thinks about renewable energy innovation. The real estate of the whole island is probably worth about as much as a square foot in midtown Manhattan. Nothing is gold-plated. The locals would undoubtably be written off as losers, too dim to move out of the outer, outer boroughs and rise above subsistence fishing. Their ratings are in the toilet! Sad!

He might ask: Why would America concern itself with people like this? What’s in it for us?

I wandered into a video store. There are a few of these in town, essentially communal living rooms with TVs where people can watch movies, or TV, or play video games. A few kids were fixated on one screen showing the Colin Firth spy movie Kingsman: The Secret Service, likely a pirated copy, badly overdubbed in Chinese. On another screen was Al Jazeera English. At the very moment I stepped inside, piped out of solar-powered speakers, I heard the anchor say the words:

“Donald Trump has been elected the next president of the United States.”

I had traveled to more remote places than this, faced higher language barriers, been lonelier, more exhausted. But at that moment, I had never felt further away from home.

A woman on Mageta Island lays out anchovies to dry in the sun. (Tim McDonnell)

I stepped outside, blinking in the blinding sunlight, my head in a fog. Little kids shouted at the muzungu to take their picture. I ignored them. I felt like I was walking on the moon.

I heard the sound of music, the same tunes as Rebecca’s soda shop but louder. I followed, and came to a kind of central square where a few guys were dancing in front of a stack of giant speakers. It was noon, and they were very drunk, and having a ball, and I envied them. At least someone is having a good time, I thought. At least we can still get drunk and dance.

As I made my way back to a hotel on the mainland that night, I thought about the Paris Agreement. It was never perfect. When the final draft was circulated, everyone knew that it didn’t work hard or fast enough to really “solve” the problem of climate change. But I always thought that what the document signified was at least as important as what it stipulated. For the first time, after two decades of labor, nearly every government on Earth agreed that climate change was real and needed to be addressed. As President Obama frequently reminded us, meaningful progress is always slow and piecemeal and unsatisfactory at first. But we find common ground where we can, and then move forward together step by step. We must continue that progress regardless of obstacles. There’s far too much at stake to take any steps backward.

Now, Trump will be the world’s only head of state who denies climate change. Who knows what will happen to the agreement itself; Trump, his statements during the campaign notwithstanding, is unpredictable, and the agreement may contain legal firewalls that could prevent him from withdrawing immediately. In any case, I hope that the American people will carry the spirit of Paris forward, in whatever ways possible, even if it’s without the support of our government’s policies. For me, that means continuing to deliver news about climate change, and working hard to hold Trump’s environmental administration fully to account.

I’m all for making America great; but to my mind, that means recognizing our responsibility to a place like Mageta Island. We cannot leave the world’s poorest people to clean up our mess.

Mahanga Beach, the main village on Mageta Island, now has a security floodlight on the main street at night, thanks to solar power delivered by overhead cables. (Tim McDonnell)

Tim McDonnell is a Fulbright-National Geographic Storytelling fellow reporting on climate change impacts to food security in Kenya, Uganda, and Nigeria. You can follow him here, on the Plateblog, and on Instagram and Twitter.